March 11, 2011 is a date no one in Japan will forget. The “triple whammy” was like nothing any other country has been subjected to, and the Japanese ploughed through it with a grace and dignity I’ve never seen in over 20 years as a journalist witnessing global pain.

The devastation was indescribable. The world had turned upside down, and everywhere there were reminders that nothing was as understood.

The damage in Ayukawa. The quake literally shifted the Earth on its axis of rotation and shortened the length of a day by a microsecond. (Source: Live Science)

Short List

Mangled cars atop dislocated roofs. Fish on the other side of shattered high street windows. Debris so mutilated it looked like piles of matchsticks left to mark where towns once stood.

60% of Kamaishi, in Japan’s northern Tōhoku region, was destroyed.

That’s only a short list of what was at least tangible. The intangible damage was immeasurable.

The sea that fed them had become a traitor, and the nuclear energy that was beneficial for decades had become a curse.

US Geological Survey said 400 kilometres of Japan’s northern coastline dropped by 2 feet.

It was like being trapped in a 4-D horror movie with no ending. Or a pause button. And yet, no length of video could capture the immensity of Japan’s triple tragedy. Earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster all rolled into one painful, traumatic ball.

New Landscape

Along the north-eastern coastline, as far as the eye could see, a new landscape so incomprehensible that survivors wandered around silently for days trying to take it all in, and looked for missing relatives as if walking through hallowed ground.

Rikuzentakata’s city hall used to stand somewhere here. This is where the tsunami came furthest inland – 8 kilometres.

And hallowed ground it was. Is. Thousands of lives were lost here, hundreds of thousands more were disrupted. Entire communities destroyed. Towns wiped out. But despite this, hopes were never extinguished. Japan pulled together and worked as a whole through the worse ordeal it could remember since World War 2. It wasn’t a question of if it would rise again – but when.

‘Kamikaze’

“Sato” met us in a small hotel room in Fukushima one sunny afternoon. His real name was irrelevant – but the story he wanted known encapsulated the Japanese spirit.

Sato was one of the hundreds working around the clock, in shifts, exposing themselves to high levels of radioactivity, risking their lives to try to contain the numerous leaks from the crippled nuclear power plant. They had been at it since March 11, and went for weeks without even knowing if their own families had survived the quake and tsunami.

Sato spoke through a translator and only said one line in English: “We are kamikaze.” They knew they were on a suicide mission, and there was both sadness and pride in his voice.

Sato had worked at the plant for over 10 years and said its current problems stemmed from design flaws. Its original American makers built it to withstand tornadoes and hurricanes, as it would have needed to in the U.S., but the design hadn’t been adapted for tsunamis, nor earthquakes, as Japan is prone to.

Sato didn’t want to waste time pointing fingers. What he seemed to want to do most of all was take accountability himself, for allowing people to “blindly believe” in what he called the “myth of infallible safety.”

“The reason why I‘m back at work is because I was an accomplice to the safety myth. This is a way to carry out my responsibility and make atonement to those people who can no longer live in their village. One day, one day, we are going to return them there…”

Recovery work continued in Kamaishi, Iwate prefecture, despite the weather.

Sato wasn’t the only one we met who was aware of not only who he was, but who he was in relation to the wider community. People had a strong sense of self, and also a deep sense of responsibility to others.

Overlooking the devastation in eastern Japan.

One For All

There was a mother in an evacuation centre who told us that after they had gotten to safety, she made her 2 young sons watch as the tsunami devoured their village below. That way, she explained, when it happens again, they will already understand the power of nature, not be rattled by it, and be better able to help their neighbours. Both sons had been having trouble sleeping ever since, but their mother believed the trauma would only make them stronger in the end.

The children’s father had been at work when calamity struck and they hadn’t seen him since. Weeks later, he walked into their evacuation centre. The waves had carried him far, and in his search for his family, he’d stumbled upon strangers needing help – and cared for them first. This sense of community permeated many of the stories of survival.

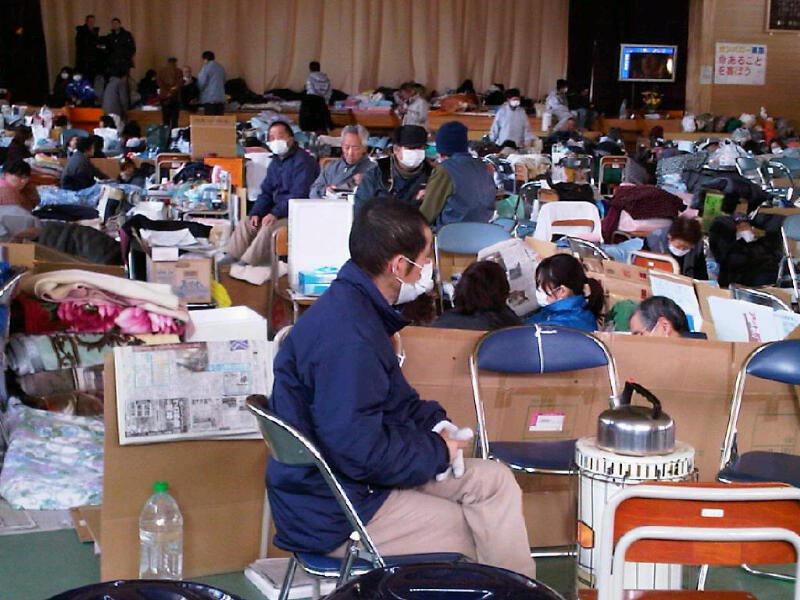

Rikuzentakata. Evacuation centre.

Respect

In school gyms and courtyards that served as temporary homes for thousands of people, families used what they could to make small enclosures, mindful to respect each other’s privacy. Shoes were neatly lined up by the entrance, and disinfecting liquids were readily available. Surgical masks were also being used; survivors were careful not to pass on any unwanted bugs to those most frail among them. Food distribution was organised, and cleaning rotas were devised by the residents themselves.

Keep Moving

Life goes on, and they were taking concrete steps to keep moving forward. Instead of allowing themselves to drown in the immense grief they were surely entitled to, many returned to work – for their own local governments – to rebuild their villages. It was a matter of honour to share the load.

Hundreds of others came from unaffected areas to volunteer their time and their services, seeing it as a matter of human duty.

Construction workers, counsellors, engineers, and even lawyers like Yukimitsu Saitu.

Yukimitsu Saitu, lawyer, volunteer.

“So many have lost the foundation of their lives,” Saitu told us.

He spent his free time going to evacuation centres helping survivors deal with the legal issues so often overlooked in such calamities. Mortgages. Debts. Inheritance. Insurance. Death certificates. What-not.

“People are damaged in all kinds of ways,” Saitu said. “I am here because I think it is important to support each person’s problems, one-on-one.”

To give concrete solutions to concrete concerns.

But no one was expected to have all the answers. Even the fledgling national government was given leeway, in the early months, with regard to its shortcomings, on the understanding that what had happened was beyond simple human comprehension.

Kamaishi, Iwate prefecture. The “world’s deepest breakwater” failed to protect residents.

Through it all, there were constant aftershocks. The worst so far measured 7.1, almost as high as the temblor that devastated China in 2008. It was like being trapped in the bowels of a ship in tumultuous seas during a tornado. The walls shook, things fell off tables, and it was nearly impossible to stay upright.

Another Jolt

Despite the expectation, life doesn’t flash before your eyes at such a confrontation with human frailty. The senses were heightened, anchoring us in the inescapable present moment. Everything seemed to happen in slow motion. At any second, the ground could cave in beneath you, and the world could crash down from above. And there was nothing you could do about it. No drowning in memories of the past, or worrying about the unfathomable future.

For survivors of the 9.1 quake just a weeks ago, there wasn’t even the sense of being weighed down by their difficult present. There was only the shaking of the earth beneath us all – and the reminder that life was truly beyond control.

Rikuzentakata.

House of Cards

We reside in a house of cards. It’s easy to forget sometimes and think we’re on solid ground, but really, nothing is unbreakable. Everything is in motion, in constant flux – even if we don’t see it or feel it. The universe is relentlessly moving, and that’s why it’s alive to begin with. How funny, we humans! Our greatest gift – the interminable instability, the impermanence, the opportunity for change – and all we do is try to pin things down. Finally accepting defeat on that matter could be our greatest triumph.

The Incalculable Summation

A magnitude 9 earthquake struck eastern Japan on March 11, 2011. An inestimable tsunami swept in and took out to sea what didn’t belong to it. The damage to a seaside nuclear facility then released radiation that no one wanted to even calculate.

Rebuilding Natori, Miyagi prefecture. Three months after the quake and much of the clearing had been accomplished.

A conversation with a Japanese woman put it all into perspective – how does one survive? It isn’t so much what you do – it depends on who you are.

#