It was a very hot day. The unforgiving kind that left nowhere to hide.

Cradled within the sweltering curves at the centre of one of the southern Philippines’ more developed cities lies a small shanty village.

It wasn’t far before its spindly walkways revealed a relatively large yard enclosed by a wire mesh fence. Everyone knew who lived in the ramshackle wooden dwelling at the back. The Miparanum brothers were neighbourhood legends.

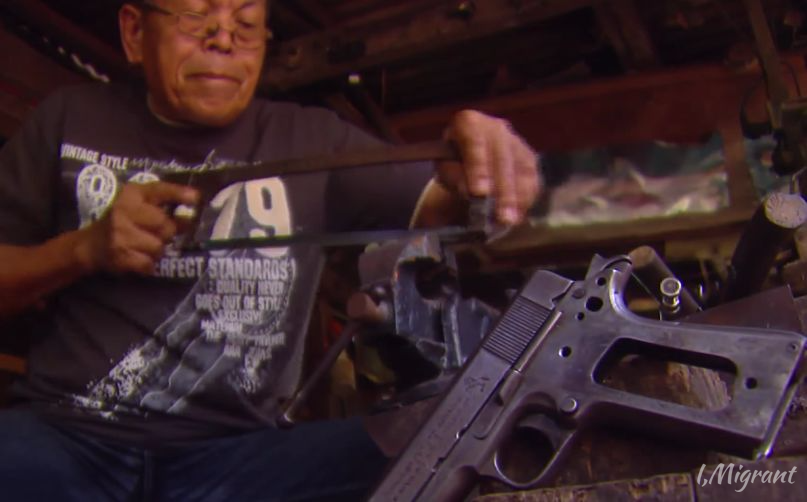

Nic and Manuel Miparanum at work.

Side by Side

Under the shade of their star-apple tree, 69-year-old Nic sat near 78-year-old Manuel, both huddled over workbenches busily handcrafting guns. Just as they’ve done for over 25 years.

Nic said he made his first weapon when he was only 10 to defend his family from thieves. “You can’t not be armed here. You always need to protect yourself,” he said.

They lived in a dangerous place, he said, and his family paid the ultimate price when his father was killed by a political rival when he was only 16.

“He wasn’t armed, our father,” Nic explained. “He didn’t stand a chance.”

That’s when he vowed he would never be a victim again.

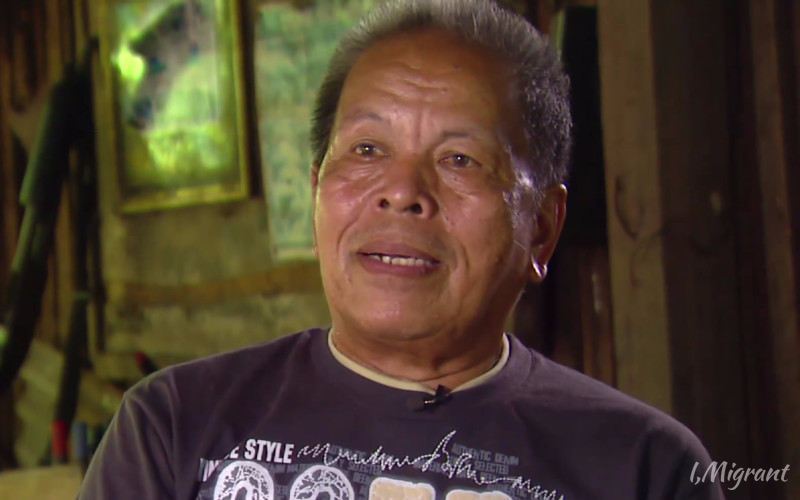

To his hundreds of clients, Nic Miparanum is a skilled craftsman.

Gun Culture

In 1986, Nic and his brother used their skills to earn a living. They now make anywhere from USD $35-$300 per weapon.

The Miparanums don’t just make guns from scratch, they can also modify any weapon according to a buyer’s specifications. Their restive province is rife with all sorts of potential customers, and their clientele ranges from soldiers to rebel fighters, warlords to ordinary citizens.

A separatist war is being waged here and feudal politics prevails. It’s also known to be a hotbed for loose firearms, which are estimated to number more than 100,000.

“It’s just the way things are,” another local resident said. “I am not from here originally, but I have been acculturated,” he went on to say.

To be armed is to level the playing field.

Family Ties

Just outside the shanty village, unmistakable signs of progress and peace are beginning to dot the landscape. Modern shopping malls are cropping up. Restaurant chains from the big cities are settling in. Coffee shops now line pavements.

But beneath all the trimmings, not much else has changed in Maguindanao, because the DNA by which the culture is defined is the same. The “family” fingerprint.

“I went after the family that killed my father,” Nic shared unequivocally. “I had to. If not, they would’ve finished us off. So I beat them to it.”

He barely batted an eyelash, unafraid to tell his story. “Why should I be? That’s the way justice works here.”

Family Feuds

The Miparanums never thought of moving away. “Here, even if you leave, whoever’s after you will go after the last remaining relative; there is no simple end to feuds,” Nic said.

He continued that eventually a feud might be resolved by a marriage arranged between the two parties expressly for that purpose. But even a marriage is no guarantee of everlasting peace. Until entire family trees are healed, it will be a neverending cycle of violence, or, one-up-manship.

Another local told us that that’s the way things would’ve played out after the 2009 massacre here, that was born of a long-standing feud between political clans, had there not been “outsiders” among the victims. At least 58 people were killed that day, more than 20 of them were members of one family.

As it is, the two powerful clans involved have already intermarried through the years, but that’s not helped in terms of finding a way for them to share power in the province.

In the cycle of local politics, the two clans simply replace each other. And politics is just another means by which they play out their generations’ old family dramas.

Peace

Nic Miparanum doesn’t believe he’ll ever live to see things change.

“This is already my destiny,” he said, speaking openly about it without fear or shame.

“I will not hide anymore, people should know the truth.”

If he had a mirror, Nic would see a look of peace actually came over his face as he said that.

“They can come after me if they want, I am ready,” he reiterated, “but I will likely get to them first.”

Nic Miparanum.

Like a man who has settled his demons, Nic smiles and looks up to the bright blue sky stretched out behind the leaves of his star-apple tree.

He has cast light on a shadowy world few understand.

He is no longer a victim, and he has survived.

*an earlier version was first published by Al Jazeera English.